WELCOME TO LOCAL STORIES

SINGAPORE

Telling the Singapore Stories

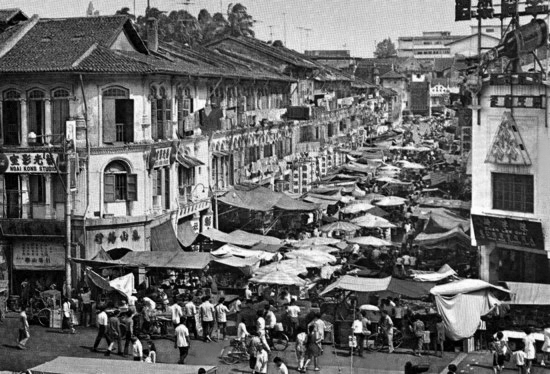

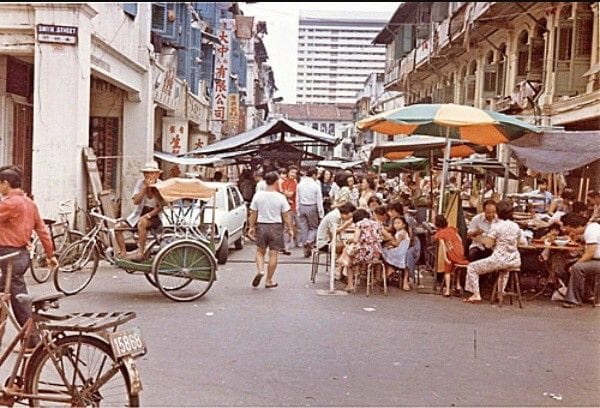

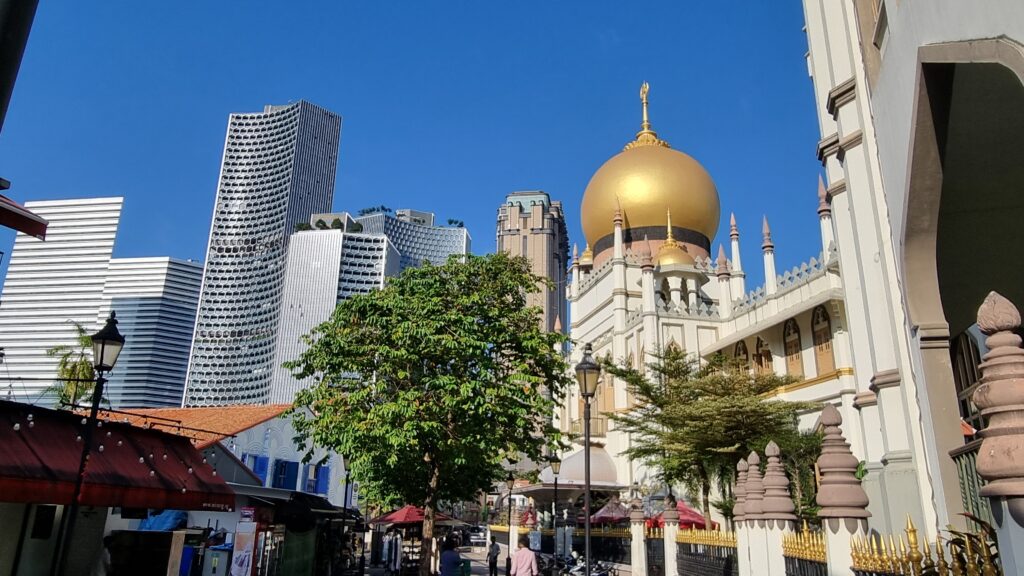

I was born and raised in Singapore and have the privilege of having lived through a good part of the history of modern Singapore itself. It’s been a remarkable journey to witness the changing landscape and the evolving characteristics of this nation.

As we move forward, we can lose many of the nuances and connections that make up the rich tapestry of the people, places and stories of Singapore. This is especially so with the multiculturalism of the various ethnicities that make up the population.

Here are some of these reflections that hopefully can provide a better appreciation and deeper understanding of our community.

LOCAL STORIES POSTINGS

GET TO KNOW YOUR SINGAPORE

Many Singaporeans have fond memories of listening to their parents, grandparents, or other relatives recount stories from their eventful past. These personal anecdotes offer a window into a not-so-distant era. We learned about Singapore’s history in school through Social Studies, which provided background knowledge of our nation’s journey. However, for many of us, learning more of our heritage and understanding the importance of preserving our collective stories often takes a backseat as we focus on building our careers and families.

What was Singapore like before the arrival of Sir Stamford Raffles? Who were the early immigrants, and what motivated them to settle here? How was life then? Who are Pickering, Crawford, Alkaff, and Eu Tong Sen, after whom roads are named? These are just a few questions that make our history so fascinating. If you like to know about these and more, here are information that can help you.

Choose one of the three option buttons below to start your local learning journey.

GET TO KNOW OUR SINGAPORE

If you have not been to Singapore or want to come again for a more immersive experience, you can also look at the 3 buttons above to start your planning.

To help you further, here are helpful links below to get the latest information on what’s happening in town.

History and Cultural Websites

And where to find them

Besides having to spend time reading hefty books about Singapore’s history and stories, one of the easiest and most practical ways to learn is by exploring the wealth of heritage websites available online. It’s quick and convenient — you don’t need to travel to the actual site, and you can log in anytime, anywhere. Many of these platforms go beyond static text and photos, offering engaging, interactive features such as videos, immersive images, and virtual tours that let you trace Singapore’s development through time.

These websites come from many forms — from official government portals, to narratives curated by museums and heritage institutions, to personal blogs and even commercial sites dedicated to preserving and sharing Singapore’s past. Below are some of the websites that you can start your journey with.

Museums and Heritage Centres

And where to find them

Our history, especially during the nation-building era, is relatively short. Luckily, Singapore is rich in museums and heritage centres that remind us of our past. However, many Singaporeans find these places less inviting, missing out on their true value. Beyond just housing historical artifacts, these spaces connect the past with the present, inspiring future generations.

Historical museums help us understand our roots, the struggles and victories that shaped Singapore, and our relationship with neighboring countries. Other museums focus on creativity and innovation, encouraging critical thinking and self-expression. These engaging, interactive spaces make learning about history, art, and science fun and accessible for all ages.

Click below for a list of museums and heritage centres, along with brief descriptions to help you explore these cultural gems.

Walking/Experiential Tours

And where to find them in Singapore

Walking tours are a unique and immersive way to learn about the past and present of selected places in Singapore. It is usually done by a knowledgeable local guide, and it allows you to interact with the guide for an immersive experience. This brings the city’s past to life, sharing fascinating stories, historical anecdotes, and cultural nuggets.

Experiential tours are for those who want more than just walking around and prefer to experience the journey.

The link below brings you to some of the types of walking and experiential tours that are available.

LIST OF HISTORY AND CULTURE WEBSITES

LIST OF MUSEUMS AND HERITAGE CENTRES