Were there Indian Army Sepoy soldiers on the Sri Mariamman temple?

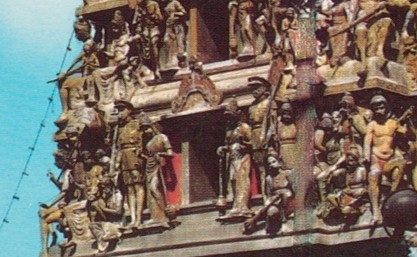

As you enter Chinatown from South Bridge Road, you will see the towering gopuram (ornamental entrance tower) of the Sri Mariamman Temple. It is the oldest Hindu temple in Singapore and is one of its most richly decorated landmarks. The gopuram has five tiers and features three-dimensional sculptures of Hindu deities in relaxed poses. And it is said to have statues of Indian sepoy soldiers wearing khaki uniforms among the deities.

But today, it is difficult to find them on the gopuram. Some pointed to the blue figures at the corners of the second tier to be them. From afar, they do look like men (though not in uniform) holding a brown rifle. But on closer look, the blue men are actually holding long swords, partially unshielded from their brown scabbards. This detail is best observed from Pagoda Street, a street that has an unfortunate misnomer, as someone seems to mistake the gopuram to be a pagoda. So, are there statues recognising the contributions of Indian sepoy soldiers at the Sri Mariamman temple? The answer is Yes and No.

The current Sri Mariamman temple was built in 1827 by pioneer Naraina Pillai. Originally, it was a modest wood-and-attap shrine; it was rebuilt with bricks in 1843. The British East India Company had earlier allotted a plot on Telok Ayer Street for a Hindu temple, but it was deemed unsuitable because there was no nearby freshwater supply for rituals. The present site was chosen instead, likely because of the underground spring around the Ann Siang Hill area, the same water source that gave the Chinese reference of Chinatown as the Bullock Water Cart place. Originally, the temple had only three tiers but was raised to its present five tiers in 1936. There were statues of the Indian sepoy soldiers standing guard in khaki uniforms and armed with rifles included on the first tier of the gopuram. These were added by craftsmen who drew on familiar figures (including colonial soldiers) when modelling the plaster sculptures.

In the 1960s, it was decided to restore and update the gopuram with more elaborate sculptures and carvings that we see today. This resulted in the removal of the sepoy statues and their replacement with figures clad in Indian traditional costumes in 1971. There was no official reason given for the removal, but during this period, there was a general move to preserve cultural and religious symbols while removing elements considered outdated, military symbols, or that no longer suited to the temple’s aesthetic or functional needs. The National Archives of Singapore holds a photographic record titled “A statue of a sepoy being removed from the Sri Mariamman Temple in South Bridge Road” dated 17 March 1971 that shows a sepoy figure being taken down from the gopuram.

The Sepoys

“Sepoy” was the term used for Indian soldiers serving in the British colonial military. They were deployed to defend colonies in Asia, including Singapore. They were crucial for maintaining law and order, constructing defences, and clearing land for settlements. The term “sepoy” is derived from the Persian word sipahi, which has been translated into the Urdu and Hindi languages as a generic term for soldier. The sepoys were the first Indians to arrive in Singapore. When Stamford Raffles and William Farquhar landed in Singapore in January 1819, their entourage included 120 sepoys from the Bengal Native Infantry as well as a motley crew of washermen, tea-makers (chai wallahs), milkmen and domestic servants. More sepoys were deployed when there was a threat of invasion from the Dutch, who were unhappy with Raffles for acquiring Singapore as a British trading post. A total of 200 Indian troops arrived from Penang, while Farquhar managed to intercept another 485 troops returning to India from Bencoolen. The area where these soldiers were quartered (the area around the junction of Outram Road and New Bridge Road) became known as Sepoy Lines, which is now the site of the Singapore General Hospital. The name has evolved into the local Hokkien and Cantonese term “See Pai Poh” or “Sei Pai Por” for the hospital, reflecting the Chinese pronunciation of “sepoy”.

Singapore Sepoy Mutiny of 1915

The First World War brought tension to colonial garrisons across Asia. Indian regiments were unsettled: many soldiers resented the idea of fighting in Europe, where the war felt far from their own concerns. Rumours spread that Muslim sepoys might be sent against the Ottoman Turks — fellow Muslims — after the Sultan of Turkey declared a jihad against the British. He issued a fatwa, or religious ruling, calling for Muslims worldwide to take up arms against the Allied powers. Neighbouring agitators encourage the soldiers to follow the fatwa.

Singapore was no exception. The 5th Light Infantry, a predominantly Muslim regiment stationed here in late 1914, was already divided and unhappy under a deeply unpopular commander. At the same time, the Malay States Guides, another regiment, were reluctant to serve overseas.

On 15 February 1915, the crisis erupted. At a parade, four Rajput companies of the 5th Light Infantry refused orders and turned their rifles on their officers. Amid the chaos, two British officers tried to intervene — one of them was shot and killed, becoming one of the mutiny’s first casualties. The rebels marched to Tanglin Barracks, freed the German military prisoners they were supposed to guard, and clashed with local forces. Civilians were caught in the crossfire, and panic spread through the city. For a brief moment, Singapore was thrown into panic as the mutineers then roamed the streets of Singapore, killing any Europeans they came across.

Order was restored only after marines from British, French, Russian, and Japanese ships landed to support local volunteers. By 17 February, the mutiny was crushed. Even though the initial crisis was over within a short time, the mutiny lasted 10 days as the authorities carried out mopping-up operations to round up the mutineers. 44 British officers, soldiers and civilians, as well as three Chinese and two Malay civilians, were killed in the mutiny. In the course of the fighting, 56 sepoys were killed. In the months that followed, courts martial sentenced dozens of sepoys to death by public firing squad or life imprisonment. The remnants of the 5th Light Infantry were eventually sent to Africa, ironically fighting alongside the Malay States Guides — the very regiment that had also refused service abroad.

Remembering the Missing Sepoys

The sepoy statues on Sri Mariamman Temple may be gone, but their story survives — in archives, in place names like Sepoy Lines, and in memories of Singapore’s early history. They remind us of the complex role of Indian soldiers in the colony: protectors, settlers, and, in moments of unrest, rebels.

Leave a Reply