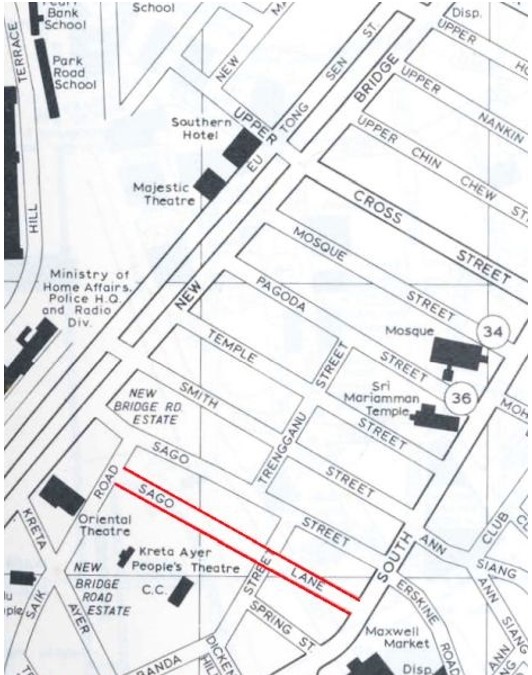

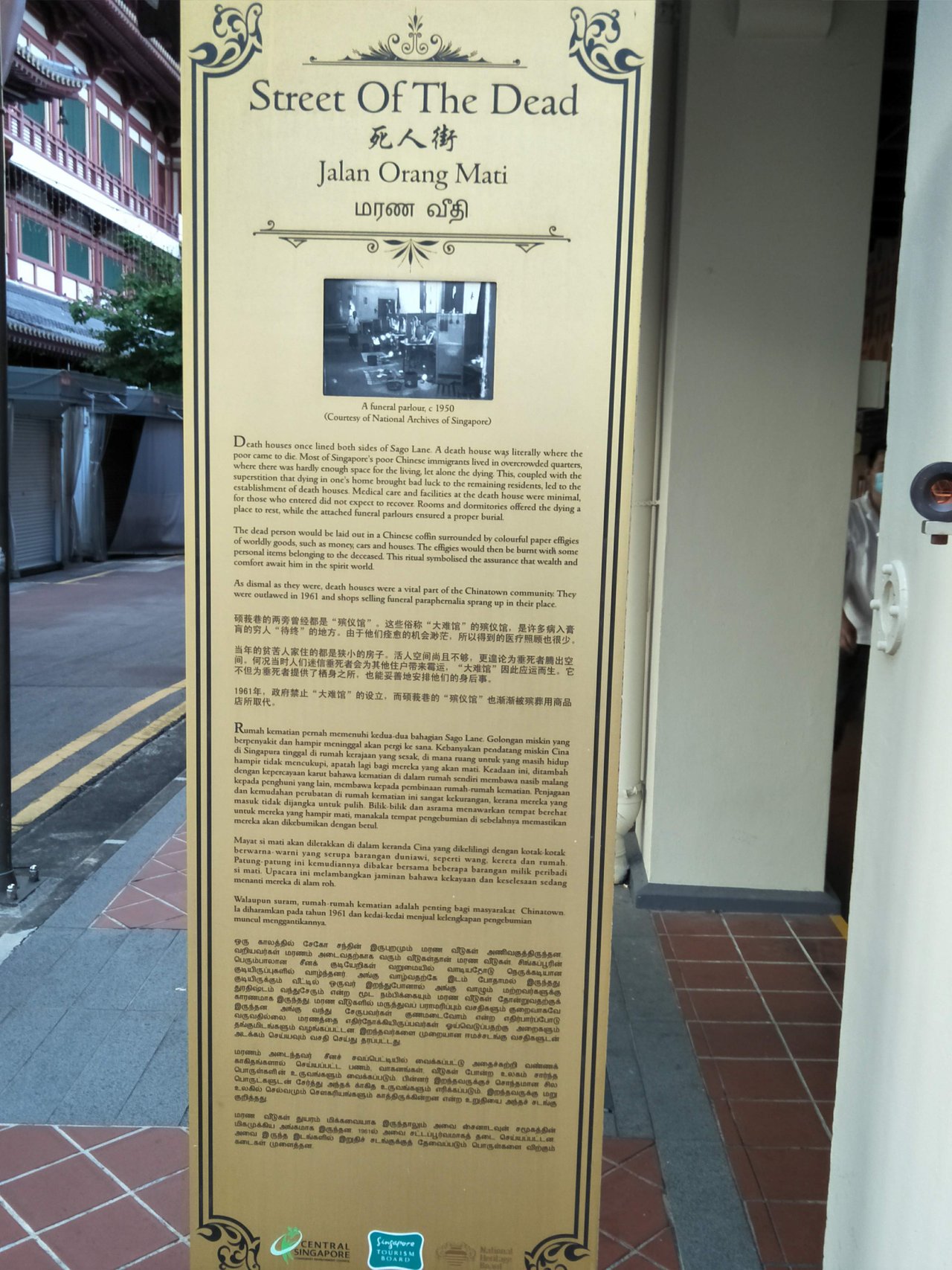

Once there was a plaque at the corner of Sago Street and South Bridge Road, explaining the history of Sago Lane and why it earned the name Street of the Dead. Today, the plaque is gone. No official explanation can be found for the reason of its removal.

Could it have been due to the morbid subject matter? Unlikely—Singapore Tourism Board has never shied away from highlighting the grittier parts of history. A more practical reason may be that the plaque was placed on Sago Street, not Sago Lane itself. Today, Sago Lane is just a short stretch tucked beside the Buddha Tooth Relic Temple, with no shophouses or stalls to draw foot traffic. By contrast, Sago Street remains lively, filled with shops and eateries, making it the more visible location. This may be the reason for the removal of the marker.

Both Sago Street and Sago Lane were named after the sago starch once processed here in the 1840s. At its peak, the area hosted 17 sago factories—15 Chinese-owned and 2 European. Sago starch, derived from the pith of tropical palms, was widely used in puddings, noodles, glue, and desserts. We are more familiar with it in the gula melaka puddings and original pearls in green bean soup and other desserts. But by the late 19th century, the industry declined, and the factories gave way to other trades.

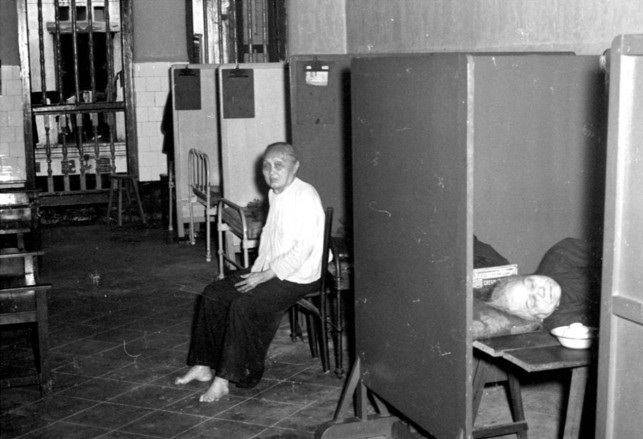

This was when Sago Lane took on a new, darker identity. As overcrowding worsened in Chinatown, the street became notorious for its death houses. These were the ostensibly nursing houses where the terminally ill checked in to die. The practice stemmed from both superstition and practicality. Cramped living conditions made it impractical and dangerous to keep the sick at home. Many distrusted colonial hospitals or could not afford them. The superstitious aspect is that it was believed unlucky to die at home, as the spirit would linger. Thus, the narrow lane became Sei Yan Kai (Street of the Dead in Cantonese).

This was when Sago Lane took on a new, darker identity. As overcrowding worsened in Chinatown, the street became notorious for its death houses. These were the ostensibly nursing houses where the terminally ill checked in to die. The practice stemmed from both superstition and practicality. Cramped living conditions made it impractical and dangerous to keep the sick at home. Many distrusted colonial hospitals or could not afford them. The superstitious aspect is that it was believed unlucky to die at home, as the spirit would linger. Thus, the narrow lane became Sei Yan Kai (Street of the Dead in Cantonese).

Death houses attracted an entire economy of related businesses: coffin-makers, undertakers, paper effigy shops, flower arrangers, and temple caretakers to Sago Lane. Rickshaw pullers also lodged here, thanks to the nearby jinrickisha station. Funerals were frequent—lavish for the wealthy, simple for the poor. Sometimes, undertakers even absorbed the cost as a charitable deed.

The street’s notoriety reached beyond Singapore. In the 1950s, BBC travelogues, The Atlantic, and even the sensationalist Italian documentary Mondo Cane featured Sago Lane. Foreign portrayals often painted it as an exotic, morbid spectacle of the East. (The link to the Mondo Caine snippet in Youtube is https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8SZoAp0UCNk). Be forwarded, it is depressing.

By the late 1950s, death houses drew increasing criticism—fires frequently swept through the shophouses, and negative international publicity embarrassed the authorities. In 1961, death houses were officially banned. The critically ill were sent to hospitals; only funeral parlours remained for the dead. The last parlour moved out in 1987.

Soon after, Sago Lane itself was cleared in waves of redevelopment. By the 1970s, most of the shophouses along the Sago area were demolished to make way for the Chinatown Complex and HDB flats. Yip Yew Chong, who once lived there, painted his memories on the walls of Chinatown, lamenting that his former home is now a car park. Others remember the bustling ecosystem of trades and the colourful, if grim, vibrancy of the neighbourhood. The once vacant space between Sago Lane and Sago Street was later redeveloped into the site of the Buddha Tooth Relic Temple.

Leave a Reply